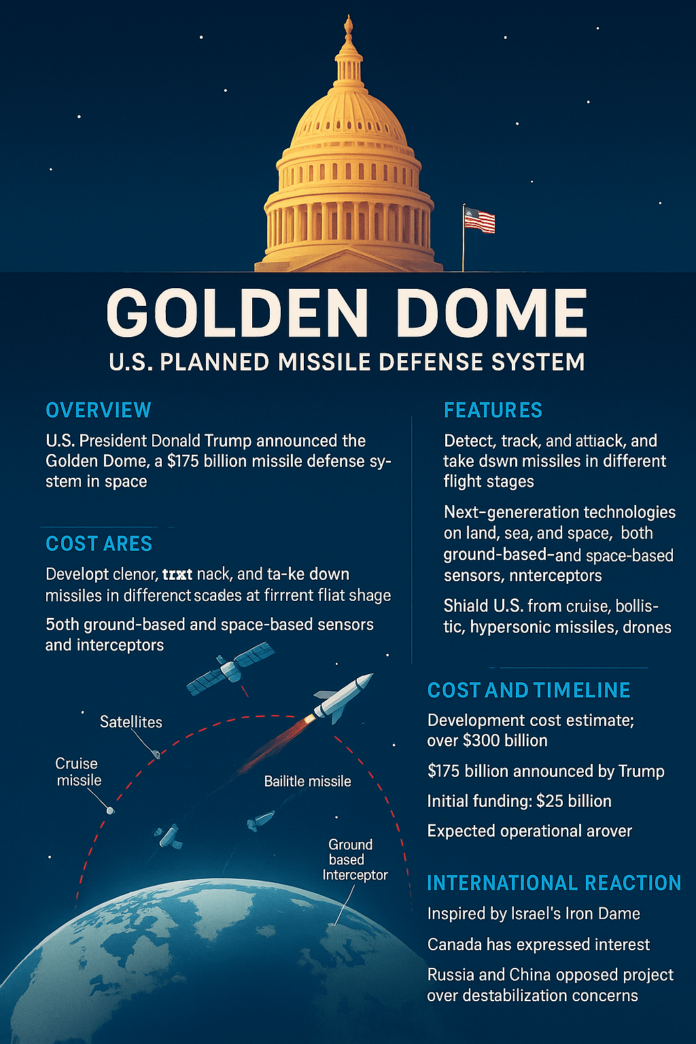

When former U.S. President Donald Trump announced the creation of the “Golden Dome,” a $175 billion missile defence initiative that aims to place American weaponry in space, it marked a bold reimagining of strategic deterrence in the 21st century. Slated to be operational by the end of Trump’s White House term, this project isn’t just about safeguarding the homeland; it signals the dawn of a new phase in the global arms race, this time stretching beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Described by Trump as essential for the “success and even survival” of the United States, the Golden Dome system promises to intercept all types of missile threats—from conventional and nuclear ballistic missiles to hypersonic projectiles and drones. With its networked defence architecture encompassing land, sea, and space components, it evokes comparisons to Israel’s Iron Dome, although with vastly broader scope and ambition.

Why This Matters

Missile defence systems like the Golden Dome are reshaping how states think about deterrence, escalation, and strategic stability. By altering the balance between offence and defence, such systems influence nuclear signalling, crisis behaviour, and long-term military planning. Understanding these concepts is essential to assessing how future conflicts may be prevented, managed, or unintentionally escalated.

This article explores the technical, strategic, geopolitical, and historical implications of the Golden Dome, and how it stacks up against other global missile defence systems.

The Vision Behind Golden Dome

Trump’s announcement placed the Golden Dome at the forefront of U.S. military innovation. Unlike traditional ground-based missile defences, the Golden Dome incorporates next-generation space-based sensors and interceptors. This would enable early threat detection, real-time tracking, and precision interception in every phase of a missile’s flight path.

“Once fully constructed, the Golden Dome will be capable of intercepting missiles even if they are launched from other sides of the world, and even if they are launched from space,” Trump stated during his announcement. According to Pentagon chief Pete Hegseth, the system will work in tandem with existing missile shields to defend against an expansive threat spectrum.

Initial funding of $25 billion has already been announced, with a projected cost between $175 billion (Trump’s estimate) and $500 billion (Congressional Budget Office). The rollout will likely span over two decades, though the administration has set a goal to make the system operational within three years.

From Ground to Orbit

Golden Dome’s innovation lies in its multi-domain architecture:

- Ground-Based Elements: The system will integrate with existing ground-based systems like the Ground-Based Midcourse Defence (GMD) and THAAD to provide terminal phase interception.

- Naval Integration: U.S. Navy Aegis-equipped destroyers will be linked to the Golden Dome network, expanding its operational range.

- Space-Based Assets: Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect is the deployment of space-based interceptors and sensor constellations. These assets will provide persistent global surveillance and allow midcourse interceptions from orbit.

By incorporating space into its defence strategy, the U.S. aims to dramatically shrink detection and response windows—a necessity in an era of hypersonic weapons and rapid-strike threats.

The Iron Dome Inspiration

The naming of the Golden Dome is no accident. It draws heavily from the legacy of Israel’s Iron Dome, a system credited with intercepting thousands of short-range rockets launched from Gaza since 2011. The Iron Dome’s layered, high-precision defence and its capacity to minimise civilian casualties have made it a symbol of effective tactical missile defence.

Trump’s administration has long admired Israeli defence innovation. However, unlike Iron Dome, which focuses on localised, short-range threats, Golden Dome is engineered for intercontinental and orbital-scale defence. The scale-up from tactical to strategic level is unprecedented.

Integrating the U.S. Arsenal

Golden Dome will not operate in isolation. It will form a new layer atop an already vast and diverse American missile defence framework, which includes:

- THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence): Targets short to intermediate-range ballistic missiles during their terminal phase.

- Aegis BMD: Deployed on U.S. Navy ships, the Aegis system provides wide-area sea-based missile defence.

- GMD (Ground-based Midcourse Defence): Designed to intercept long-range ballistic missiles during their midcourse trajectory.

The Golden Dome, with its real-time satellite surveillance and space-based kill vehicles, will add unprecedented reach and flexibility.

Global Comparison: Who Else is Building Missile Shields?

To understand the transformative potential of Golden Dome, it’s important to compare it with existing and developing missile defence systems around the world:

Israel:

- Iron Dome (short-range rockets)

- David’s Sling (medium-range threats)

- Arrow 2/3 (long-range ballistic missiles and space threats)

Russia:

- A-135 & A-235 systems protect Moscow

- S-400 and S-500 Prometey offer air, cruise, and ballistic missile defence, with claims of anti-space capabilities

China:

- HQ-19 & HQ-26 provide regional BMD capabilities

- DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicles could challenge traditional missile defence

India:

- Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) Program Phase I (for SRBM threats) and Phase II (for ICBMs) under development

- Acquired S-400 from Russia

South Korea & Japan:

- Use THAAD and Aegis systems in coordination with the U.S. to counter North Korea

While several of these systems incorporate multi-layered capabilities, none currently include deployed space-based interceptors, placing the Golden Dome in a unique class.

International Response: Alarm Bells in Moscow and Beijing

Trump’s announcement did not go unnoticed by global adversaries. Russia and China issued a joint statement condemning the plan as a “deeply destabilising” development. They argued that the Golden Dome could weaponise space, turning it into a new battleground.

“The system explicitly provides for a significant strengthening of the arsenal for conducting combat operations in space,” said a Kremlin communiqué. The fear is not just about technological escalation but about strategic imbalance: a functional space-based missile shield could neutralise the nuclear deterrents of adversaries, prompting them to invest in first-strike capabilities or counter-space weapons.

Canada and Allied Interests

The Golden Dome is not strictly a unilateral shield. Trump hinted that Canada has expressed interest in becoming a partner. Given NORAD (North American Aerospace Defence Command) already includes Canada in continental airspace defence, integration into the Golden Dome framework could be a logical extension.

Such interest may spread among NATO allies or Indo-Pacific partners. Japan and Australia, both aligned with U.S. strategic goals and under threat from missile-capable adversaries, could become collaborators or beneficiaries.

Strategic Implications and Risks

Weaponisation of Space

The most contentious aspect of the Golden Dome is its space-based component. Though the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prohibits the deployment of nuclear weapons in space, it does not ban conventional weapons. By deploying interceptors and sensors in orbit, the U.S. could redefine the boundary between peaceful space use and militarisation.

This could provoke an arms race in space, with nations investing in anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons, orbital lasers, or even kinetic bombardment systems.

Technological Feasibility

Deploying space-based interceptors comes with logistical and technical hurdles. Interceptors must be small enough to launch, durable enough to survive in space, and fast enough to engage targets at thousands of kilometres per hour. Precision tracking, energy supply, and data transmission are all engineering bottlenecks.

False Confidence?

Critics warn that overreliance on such systems could lead to a false sense of security. No missile defence is infallible. Saturation attacks, decoys, and low-flying cruise missiles could still pose significant threats.

From Star Wars to Golden Dome

Golden Dome is not the first U.S. attempt at a space-based missile shield. During the Reagan era, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), dubbed “Star Wars,” proposed space lasers and orbital interceptors. While SDI remained mostly theoretical, it laid the groundwork for research into missile defence.

Post-Cold War developments, especially under George W. Bush, saw the deployment of GMD and the revival of interest in orbital systems. Trump’s Golden Dome is arguably the most concrete step toward realising Reagan’s original vision.

Domestic Considerations and Cost Debate

With an estimated price tag ranging from $175 billion to $500 billion, Golden Dome is likely to be one of the most expensive defence projects in American history. Critics argue this money could be better spent on cyber defence, homeland security, or conventional deterrence.

Supporters, however, see the project as an essential investment. The logic is simple: one successful interception of a nuclear ICBM could save millions of lives and trillions in economic damage.

Future of the Golden Dome

Much will depend on political continuity. If future administrations choose to defund or delay the project, it could face the same fate as SDI. However, the increasing pace of missile proliferation and hypersonic advancements by Russia, China, and even North Korea may keep the pressure high for rapid deployment.

Technological breakthroughs in miniaturisation, space propulsion, and AI-driven threat detection could also accelerate development timelines.

Conclusion

The Golden Dome represents more than just another layer of American missile defence. It is a declaration that space is the next frontier for strategic dominance. By attempting to secure the high ground, the United States seeks to create an umbrella of invulnerability over its territory and allies.

Yet, this ambition comes with profound risks: diplomatic backlash, space militarisation, and a potential global arms race. As with any transformative defence technology, success will be measured not just by engineering prowess but by the geopolitical balance it creates—or disrupts.

In a world where hypersonic missiles travel at Mach 10 and orbital drones are no longer science fiction, the Golden Dome may soon be less about ambition and more about necessity. Whether history will see it as a protective shield or the spark of a new space race remains to be seen.