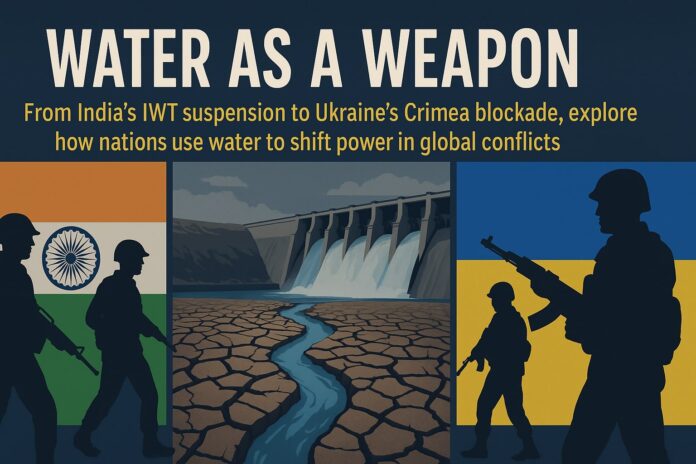

India has suspended the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan for the first time in its 65-year history, following a terrorist attack in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir that killed at least 27 civilians. But it is not for the first time that a country has done it. Neither is it the first time that India has stopped the Indus water from going to Pakistan.

Throughout history, water has been used as a strategic weapon. Controlling or denying access to water cripples economies, displaces populations, and pressures governments without firing a single shot. In 1948, shortly after Partition, India briefly halted the flow of the Indus River into Pakistan, prompting an international scramble that led to the Indus Waters Treaty. In the Middle East, Turkey’s construction of massive dams on the Euphrates has raised tensions with downstream Syria and Iraq. More recently, during the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Ukraine cut water supplies to Crimea, and the destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam in 2023 caused a humanitarian and environmental catastrophe.

Using water as a weapon carries immense risks, though. It violates international humanitarian norms, escalates conflicts, and often causes long-term ecological damage. Escalatory statements from Pakistan (like son of former Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari) are worsening the situation instead of bringing talks to the table. India’s justified responses after deadly terror attacks are met by Pakistan with nonchalance. Historical Pakistani response may have made this IWT suspension necessary on India’s part. Yet, as climate change intensifies scarcity, the temptation to use water access as leverage is likely to grow. From withholding river flows to sabotaging dams, water remains one of the most powerful and dangerous tools in geopolitical disputes.

Analysing Indus Water Treaty Suspension

The suspension of the IWT signals India’s move towards asserting hydro-hegemony over the Indus River system, challenging a treaty that many now view as outdated in the face of new climatic, demographic, and political pressures.

The IWT, brokered by the World Bank in 1960, allocated the Indus system’s western rivers to Pakistan and eastern rivers to India but failed to account for environmental concerns or equitable ecosystem management. Originally crafted to manage colonial-era infrastructure disputes, the treaty has struggled to adapt to modern realities.

India’s growing water crisis, intensified by climate change and upstream activities by China and Nepal, has driven Delhi to complete major projects like the Kishenganga and Ratle dams, straining relations with Pakistan in the recent past. While Pakistan can reject renegotiations, India’s dominance as the upper riparian leaves it with few options.

The treaty’s suspension signals a broader shift: moving beyond colonial-era bureaucratic control towards recognising ecological rights and the needs of marginalised communities. Rather than a cause for despair, the collapse of the IWT offers an opportunity to rethink and reform how vital shared water resources are governed across the subcontinent.

Historical Examples

Indo-Pakistan, 1948 – Indus River Blockade Post-Partition

Following the partition of British India in 1947, the Indus River system became a major point of contention between the newly formed states of India and Pakistan. In April 1948, India exercised its upstream control by temporarily halting the flow of water from the Ferozepur headworks to Pakistan’s Dipalpur and Upper Bari Doab canals.

This move, though short-lived, had a profound impact. Pakistan, largely dependent on these canals for irrigation in its western Punjab, faced immediate agricultural distress. India’s action was framed as asserting proprietary rights, while Pakistan appealed based on prior usage. International concern, particularly during the early Cold War years, led to negotiations facilitated by the World Bank, eventually resulting in the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty in 1960.

Yet, this incident remains a reminder of how water access can be used as a direct political weapon during moments of high tension.

Turkey–Syria–Iraq, 1990 – Euphrates River Cutoff During Atatürk Dam Filling

In the late 20th century, Turkey’s ambitious Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) sought to develop the Euphrates and Tigris river basins through a network of dams and irrigation systems. One of its key projects, the Atatürk Dam, led to significant regional tensions. In January 1990, Turkey temporarily cut off the flow of the Euphrates River for approximately one month to fill the dam’s reservoir.

Downstream countries Syria and Iraq, which rely heavily on the Euphrates for agriculture and drinking water, accused Turkey of weaponising the water supply. This move intensified already fragile relations and triggered fears of long-term water insecurity in the region. Although Turkey argued that it had informed its neighbours in advance, the episode exemplified how upstream control over major rivers could be used to exert political pressure without the need for direct military confrontation.

China–India, 2017 – Suspension of Brahmaputra Flood Data During Doklam Standoff

More recently, water was quietly weaponised during the 2017 Doklam standoff between India and China. Normally, China provides India with hydrological data on the Brahmaputra River during the monsoon season to help manage flood risks in India’s northeast. However, during the border confrontation at Doklam, China suspended this data sharing without any official explanation.

The disruption severely hampered India’s ability to forecast and manage floods, endangering communities along the river. Although China framed the suspension as a “technical” issue, the timing made it clear that the move was intended as subtle diplomatic retaliation.

Ukraine’s Water Blockade of Crimea

After Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Ukraine took a bold and controversial step: it closed the North Crimean Canal, which supplied 85% of Crimea’s freshwater needs. As a result, the peninsula faced severe water shortages that crippled agriculture, drinking water supplies, and industry.

Ukraine justified the blockade as a non-violent means to resist Russian occupation, arguing that an occupying power is responsible for providing basic services under international law. For Russia, however, the water blockade represented a humanitarian crisis and a major logistical headache.

Moscow eventually had to invest billions of roubles to dig wells, build desalination plants, and even propose plans to divert water from the Russian mainland. The 2014 blockade showed how cutting water supplies could become a tool of non-kinetic resistance, applying pressure without open combat.

Destruction of Nova Kakhovka Dam, 2023

The stakes escalated further in June 2023 when the Nova Kakhovka dam in Russian-occupied southern Ukraine was destroyed. The breach unleashed catastrophic flooding along the Dnieper River, submerging towns, villages, and farmland on both sides of the frontline. Thousands of civilians were displaced, ecosystems were devastated, and the cooling systems for the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant were put at risk.

Both Russia and Ukraine blamed each other for the destruction, though investigations remain inconclusive. Regardless of attribution, the event underscored a terrifying new reality: in modern conflicts, large-scale water infrastructure can be weaponised to create mass civilian suffering, disrupt economies, and alter the military landscape. Nova Kakhovka’s destruction is widely considered one of the largest environmental disasters of the Russia–Ukraine war.

International Law and the Grey Zone of Water Warfare

Under the Geneva Conventions, attacks on infrastructure indispensable to civilian survival, including water facilities, are explicitly prohibited. In theory, dams, reservoirs, and irrigation systems should enjoy protected status. However, the realities of modern conflict expose significant loopholes. Warring parties often justify attacks by claiming military necessity, for instance, suggesting that water systems are dual-use targets supplying enemy troops.

Strategic disruptions like Ukraine’s 2014 water cutoff to Crimea fall into a legal grey zone; so does India’s suspension of the IWT. Non-violent but devastating, such actions blur the lines between legitimate resistance and humanitarian harm. Similarly, withholding hydrological data, sabotaging infrastructure without direct violence, or using environmental manipulation all complicate legal enforcement.

The Russia–Ukraine conflict shows that water weaponisation is no longer hypothetical. It’s a grim reality that demands stronger international safeguards and enforcement mechanisms. As climate change intensifies resource scarcity worldwide, protecting water infrastructure must become a priority, not just for humanitarian reasons but for the stability of global security itself.